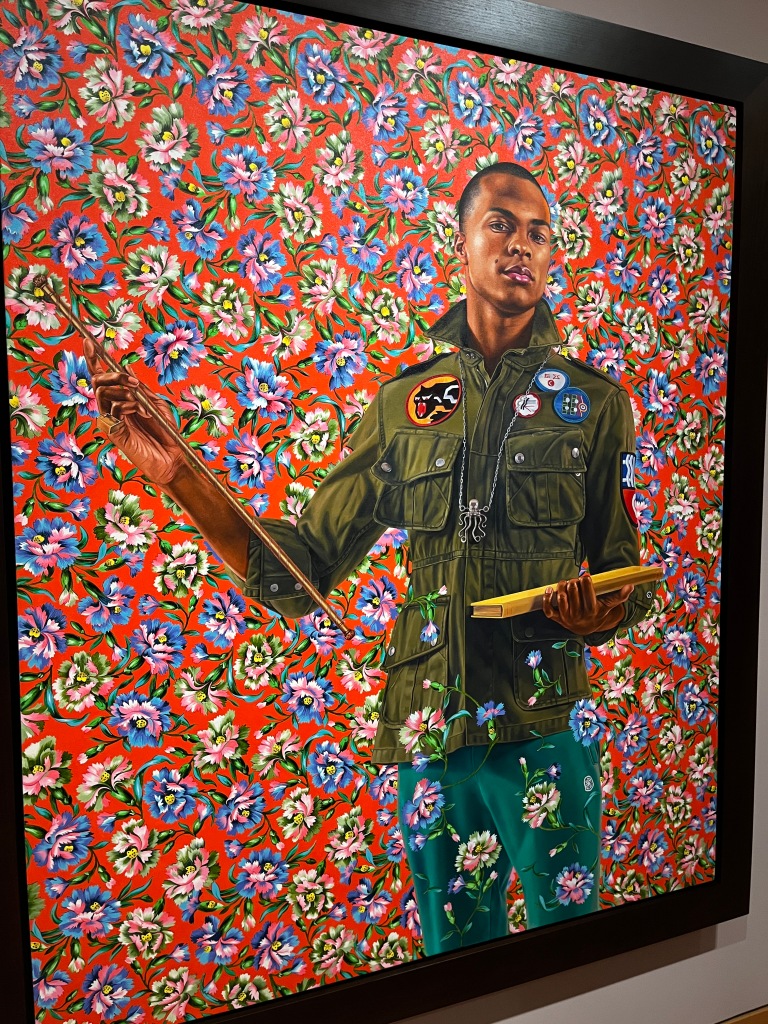

In the recently reimagined American Galleries at the Seattle Art Museum, we’re presented with a monumental early 20th-century work by Thomas Eakins, hung beside a contemporary painting by Kehinde Wiley.

William Smith Forbes is a long way from home and seems a bit out of place. Meanwhile, Anthony of Padua seems at ease.

Forbes was a surgeon back in Philadelphia and in 1882 was arrested for buying cadavers stolen by grave robbers. At trial, Forbes explained that physicians were required to have a thorough knowledge of anatomy, and yet laws made it impossible to obtain a sufficient number of cadavers. The incident led to important changes in the law.

Forbes is a white guy painted by a white artist met here by Anthony of Padua, a black guy painted by a Black artist.

On the table in the Forbes painting is a skull, perhaps one robbed from a Black cemetery in Philadelphia, a city with more than a few Black residents at the time, some of whom studied at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts with Eakins.

If they lived at the same time, Eakins might have just as well painted the figure in Wiley’s painting, although wouldn’t be inclined to so much imagination and reinterpretation. It’s harder to imagine how Wiley would treat a subject like Dr. Forbes.

Born in Los Angeles and based in New York City, Wiley is perhaps best known for painting the official portrait of the first Black President of the United States, Barack Obama. Here Anthony of Padua consists of a reimagining of a stained glass work in France by Ingres. While the work by Ingres depicts Saint Anthony holding the infant Christ, a Bible, and a lily in a display of poverty and humility, Wiley reimagines the scene by showing a contemporary figure with symbols of worldliness and power.

According to the museum label, “Wiley is interrogating the conventions of portraiture that artists comfortably partake in and questioning the silent rules of art history.”

A striking example of how Wiley uses history to opine on the present came when he visited Richmond, Virginia, and became interested in the monuments to the lost cause of the Confederacy. Wiley went on to create Rumors of War, a thirty-foot-tall statue of a young black man sporting jeans and dreadlocks, modeled on a statue of J. E. B. Stuart, a Confederate Army General.

In the aftermath of the George Floyd murder, another statue in Richmond, this one of Robert E. Lee, became a target for graffiti and protests, and in acts of vandalism and light projections, became a work of art in itself. Wiley’s largest work of art to date, Rumors of War seemed an appropriate anecdote and now resides outside the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, not far from General Stuart. The monument to Robert E. Lee has since been removed.

So what are the connections between the figures we see in Anthony of Padua, Dr. Forbes, Thomas Eakins, and Kehinde Wiley? Why are we looking at them together in the recent reinstallation and reimagination of American art in this West Coast city?

To a casual observer, perhaps the story here is that terrible things happened in the past and we are rising above history, or fighting through it. Even then, the contrast is striking.

Both figures are elevated in their surroundings. They are both of a size that commands attention. One couldn’t be more dark and serious and it would be hard to make the other more colorful and boisterous.

One serves here as a symbol of the old ideas of what constitutes American art and together the two paintings represent a slice of how we’re thinking about it now. That’s one of several stories being told from this display, but any story about Eakins gets lost in the changing interpretations.

Removed from a time and place and controversies of his own, the subject of the Dr. Forbes painting weighs considerably heavier here than the work or intent of the artist. Sure this is a painting of an old white guy, and many of Eakins paintings were (although he did paint works depicting Blacks, most notably a portrait of artist Henry Ossawa Tanner), but as with most works featuring people, the art can become lost in the subject over time.

So what is the story of Eakins?

It’s easy to conclude, perhaps incorrectly, that Eakins wasn’t as bold in his interpretations and approach as Wiley. A master at capturing a contemplative state, in many of his works, the amount of authentic detail, let alone blood, scalpels, and other instruments, shocked audiences. Yet, we don’t come away with much information from this particular installation. And to be fair, perhaps for too long museums in the U.S. have presented American art as mostly white art and that’s part of the point here.

Yet, what struck me is the phrase on the label used to describe Wiley’s work, could probably be said about Eakins. Imagine reading:

“Eakins is interrogating the conventions of portraiture that artists comfortably partake in and questioning the silent rules of art history.”

Does it fit? What do you think? Comments welcome.

Discover more from Urban Art & Antiques

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.