A museum conservator once suggested to me that landscape paintings are boring. I don’t think it was the artistic merit of the genre she was questioning. Rather, it was the lack of ambiguity that rendered them forgettable. If each revisit offers the same experience—no matter how compelling the initial encounter—it fades quickly. Often, the more immediate pleasure a painting offers, the more likely it is to fail in sustaining intellectual curiosity.

Sally Cleveland’s current exhibition, Wolf Moon at Augen Gallery, challenges that very notion. On opening night, I found myself looking—looking harder—and again, with heightened intensity.

The scale demands it. Painted in different mediums over hand-sanded gessoed paper and then cut down with generous margins, most of the work is no larger than a Christmas card; some are as small as those contemporary instant-print photos. Inevitably, I leaned in close, squinting as though reading a book with small text and narrow leading.

In her seminal book Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, Barbara Novak coined the term “Grand Opera” to describe the sweeping artworks of the Hudson River School. Cleveland’s new series stands in stark contrast to such grandeur—minuscule in scale and introspective in subject. If grandeur strikes out, gravity draws in.

Cleveland notes that her sources are often memories, imbued with emotion. It was never her intention to develop an exhibition with a narrative arc. Yet, when her recent works are grouped together, they reveal an underpinning: an affinity for a sense of becoming. The place need not be beautiful. In fact, it’s due to the innate modesty that when the right moment briefly holds everything together, the scenery suddenly becomes interesting in its own peculiar way.

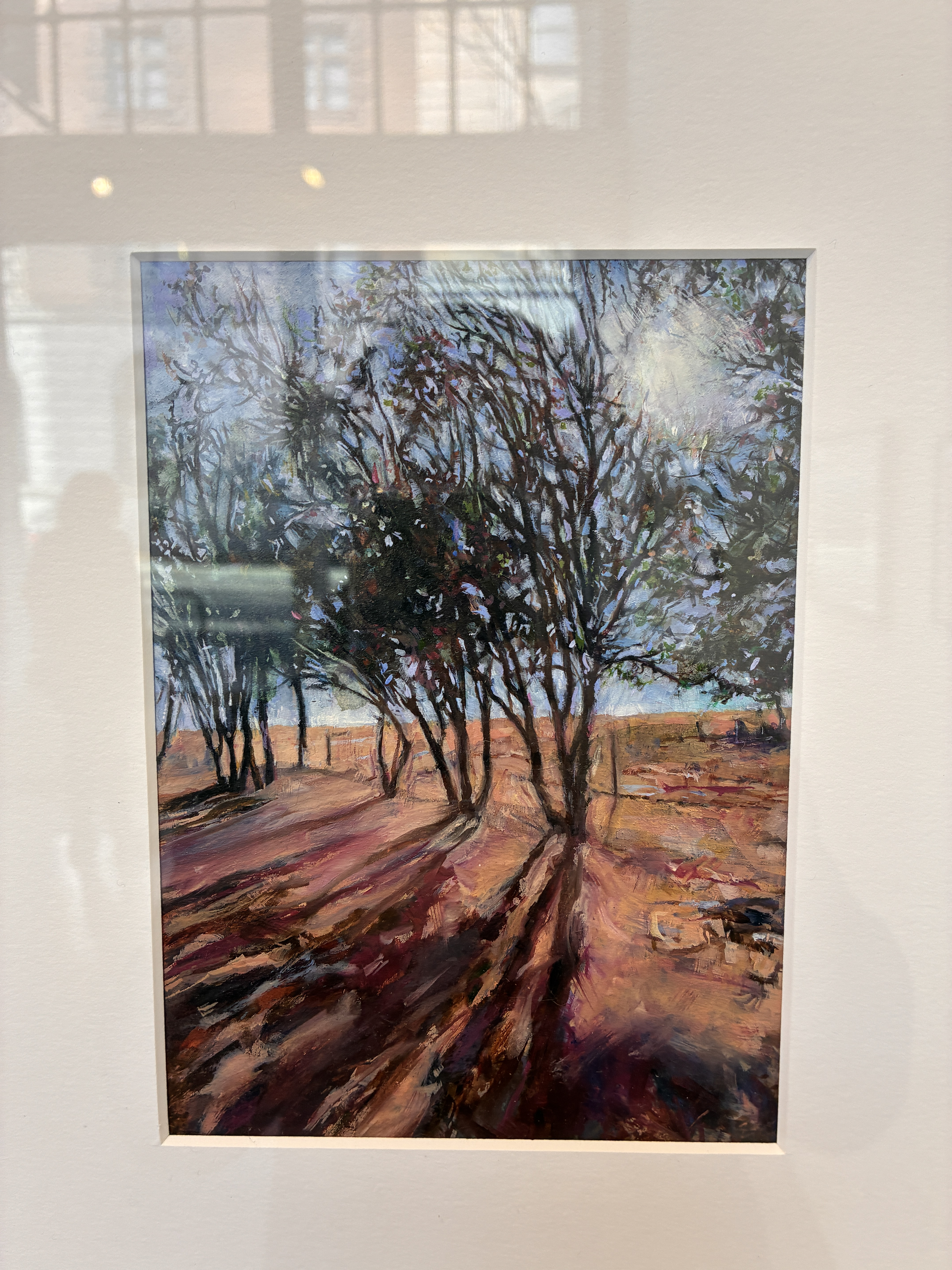

This is especially true in the work Central Oregon Tree Lines. A quiet landscape, illuminated by a bright yet low-angled sun, reveals its northern, high-desert geography. But it’s the backlit tree branches and their warm shadows that demand our attention. The shadows gather like dancers in motion, as if ready to shapeshift with the whistling wind and ever-descending sun.

That sense of becoming introduces an enigmatic paradox of being decisive and nondescript at the same time. There’s something about a specific moment, in a specific place, that only Sally’s painting can convey; despite the setting being otherwise unmarked, often intrinsically unpicturesque. It’s as though our sensibility is drawn through a small window, not just to witness the scenery, but to feel the longing within.

In Dead Broke in Idaho With Sunset, glowing orange clouds may be the initial draw, but my eyes rest on a lone car, headlights piercing forward, dashing through the foothills of a viridian mountain range. Perhaps miles of night driving still lay ahead. I wonder if the driver ever looked up, and slowed down.

The humanized landscape recurs throughout the exhibition. Human presence—be it a forlorn gate or a painted road median—imbues each image with a rhythmic tension between two opposing forces that belie the show’s apparent quietude. On one hand, nature is organic, untamed, and random. On the other, there are subtle marks of our presence—orderly, imposed, inorganic. Also in Dead Broke in Idaho With Sunset, a car races single-mindedly toward its “destiny,” set against the backdrop of aimless, fleeting clouds. In Another Road to Nowhere, cracked pavement splits across a yellow median with theatrical flair, echoing feathery clouds above. October View North may be the most distinctly Portland piece in the show: jagged rooftops intersect and crisscross the pictorial plane, only partially obscured by brilliant autumn foliage in every direction.

My favorite piece is Salem, Oregon / Darkness. To conjure poetic realism within such tight spatial limits is no small feat—but to do so while maintaining a painterly looseness is even more rare. Cleveland applies broad strokes freely, as if working with ample room. That abandonment is balanced with the extreme care of the translucent surface. Here, shadows ripple through a transient stream, glinting in jewel-toned shades. The fluid motion, color, and light in the water sharply contrast with the static building behind, partly lit despite it being daytime.

This painting is an ode to the Pacific Northwest’s rainy days of late fall—especially for those willing to brave the wetness. The last bright leaves, the calming sound of raindrops, and the cold, refreshing air all come together as a not-so-distant memory. Cleveland proves that even within a 4-by-6-inch frame, gestures and tenderness can coexist.

You can see the works at Augen Gallery at 716 NW Davis St in Portland through April 26, 2025.

Discover more from Urban Art & Antiques

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I totally get why landscape paintings can seem boring or forgettable – especially when they feel flat or lack deeper meaning. I used to feel the same way, just like the museum conservator mentioned. But that changed completely when I saw a Jan van Goyen painting in person. The way he captured light and atmosphere, the subtle details – it was like seeing a landscape for the first time. Suddenly, I understood how these works could carry so much emotion and depth.

Reading this blog post really resonated with me because it mirrors my own experience. What I once dismissed as just “pretty scenery” became something far more meaningful. A reflection of memory, longing, and quiet introspection.

LikeLiked by 1 person