Few art institutions can launch a new grand installation of American Art in both thematic and chronological order, without feeling contrived. The Met is an exception. The new American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art takes 30,000 square feet of the second floor, spreading over 26 galleries. Together with multi-leveled periods rooms, decorative arts on periphery balconies and a sculpture garden, Met still reigns the field of American art.

Few art institutions can launch a new grand installation of American Art in both thematic and chronological order, without feeling contrived. The Met is an exception. The new American Wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art takes 30,000 square feet of the second floor, spreading over 26 galleries. Together with multi-leveled periods rooms, decorative arts on periphery balconies and a sculpture garden, Met still reigns the field of American art.

Considering that the previous American Wing was installed in 1980, it shows how much the curatorial knowledge and preferences on exhibitions have evolved within the last few decades. The grand hallways, which are still abundant in many older art institutions such as the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, though impressive when gigantic historical paintings are hang alongside, have proven to lack of versatility to accommodate variety of subjects, sizes or mediums. The new American Wing, divided into galleries of various sizes, embraces both grandeur and intimacy. It carries the sense of history and aesthetics into the intrinsic flow of the galleries; yet it remains flexible enough to let impatient visitors skip the curatorial connections and directly purvey into areas that matter to them the most. It is a marvelous feat for an art installation of such comprehensive scale.

Yet, it takes no time for visitors to realize the new American Wing has a strong emphasis in the 19th century. Although the new addition of Ashcan school extends the time period of the whole collection into 1920’s, regionalism, abstract and other forms of mid-century modernism are not included.

Following the direction of the hanging eagle by William Rush for St. John’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in 1803, passing many faces of the Colonial period, one would inevitably enter the grand gallery with Emanuel Leutze’s monumental “Washington Crossing the Delaware”, flanked by two other works: Church’s 1859 “The Heart of the Andes” and Albert Bierstadt’s 1863 “The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak.”

Such an arrangement appeared in the Metropolitan Fair of 1864, a fund-raising exhibition near the end of the Civil War. The exhibition photos, captured by Mathew Brady, were re-discovered by the Met curator, Kevin Avery, from some archives at the New-York Historical Society . The original frame, although slightly out of focus and lack of three-dimensional details, came to light for the first time to the public. Such an incidence became an unpredictable force that single-handedly changed the course of designs of American Wing Galleries.

Placing Leutze’s “Washington Crossing the Delaware” as the centerpiece of the whole collection relays a profound message in the scholarly assessment of 19th century American paintings. Neither historically correct (one docent listed many inaccuracy in the painting from the not-yet-conceived American flag to the ice on Delaware River), nor considered high-brow (the mannered theatrical treatment had long alienated critics since the 19th century), the painting, nevertheless, speaks of essence of Americana in public mind: a subject based on romanticized history mixed with patriotism and a design of grandeur with an engaging narrative. The fact that Leutze has made so many “mistakes” in one painting only adds the charm of it so that school teachers and parents could bring historical correctness on top of a strong cinematic display.

The gallery “Portraiture in the Grand Manner” carries the kind of glamour of Leutze to the end of the 19th century. The opulent life of high society women in the gilded age provides ample opportunities for Sargent to continue the tradition of painting the likeness of aristocracy as the unquestionable artistic descendant of van Dyck and Velazquez. One has to look up as if being called upon by the sitters; yet the superlative technicality is hampered by the necessity of establishing the social status: I was amazed, but not moved. Only in Madame X, a painting not though commission, the unconventional pose sheds light to an inner psyche of the sitter.

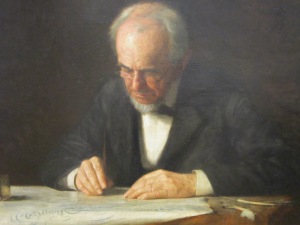

Only a handful of painters receive the elevated status in the gallery presentation as Sargent. There is one gallery devoted to John Singleton Copley and one shared by Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins. If Sargent’s societal portraiture has the kind of coolness of keeping the viewers at a distance, Eakins’ painting of his father “The Writing Master” draws one into a world of a purified realism. The contrast between the sharp focused hands and forehead and a slightly off-focused foreshortened face speaks of a near photo-realistic precision and anatomical excellence. The sitter’s concentration on writing is locked in a moment of perpetuity. Through the artist’s vantage point, we are at a close distance, perhaps with the knees slightly bent to watch the wonders of handwriting. It is Eric’s favorite portrait in the whole collection.

Only a handful of painters receive the elevated status in the gallery presentation as Sargent. There is one gallery devoted to John Singleton Copley and one shared by Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins. If Sargent’s societal portraiture has the kind of coolness of keeping the viewers at a distance, Eakins’ painting of his father “The Writing Master” draws one into a world of a purified realism. The contrast between the sharp focused hands and forehead and a slightly off-focused foreshortened face speaks of a near photo-realistic precision and anatomical excellence. The sitter’s concentration on writing is locked in a moment of perpetuity. Through the artist’s vantage point, we are at a close distance, perhaps with the knees slightly bent to watch the wonders of handwriting. It is Eric’s favorite portrait in the whole collection.

Another Eakins’ painting “The Chess Players” benefits from the rearrangement so that it won’t be dominated by paintings of much larger size. The amount of details captured in this small gem is superior especially considering the setting is under dim light and the whole picture is harmonized under warm dark paint. Gustav Flaubert, who once commented that a writer should be able to describe a horse so it could be distinguished from every other horse in Paris, would agree with Eakins’ interior setting. It would not be hard to find the decanters and glasses, cabinets and chairs to recreate such a Victorian parlor. From the label, it reads the painting was the first artwork by any living artist to enter the collection of Metropolitan Museum of Art. (It was given as a gift by the artist in 1881.)

Another Eakins’ painting “The Chess Players” benefits from the rearrangement so that it won’t be dominated by paintings of much larger size. The amount of details captured in this small gem is superior especially considering the setting is under dim light and the whole picture is harmonized under warm dark paint. Gustav Flaubert, who once commented that a writer should be able to describe a horse so it could be distinguished from every other horse in Paris, would agree with Eakins’ interior setting. It would not be hard to find the decanters and glasses, cabinets and chairs to recreate such a Victorian parlor. From the label, it reads the painting was the first artwork by any living artist to enter the collection of Metropolitan Museum of Art. (It was given as a gift by the artist in 1881.)

In the last gallery, all the eight artists in the landmark 1908 Macbeth Galleries exhibition are presented even though Ernest Lawson, Maurice Prendergast, and Arthur B. Davies were not in the league of social realism. If the homogeneity and harmony marked the antebellum artworks in the previous galleries, the thematic organization becomes loose in galleries (except American Impressionism) which from the gilded age to the eve of the World War 1.

The American Wing has undergone a five-year, three-phase renovation. It was in May of 2007 when I first visited the previous American Wing, just before the renovation started. Many galleries were presented in the salon style. I was overwhelmed, although I can still remember the “wow” effect when seeing Edwin Church’s “the Aegean Sea.” During the period of renovation, I have moved in and out of New York. Even though I had frequented the Met many times when I lived there, much of the American galleries were closed for most of the time. Thus, to return to the Met to see the completion of the galleries is like fulfilling a mission that is long overdue.

In the end, I was greeted by a surprising find — Dwight William Tryon’s “Early Spring” in the shimmering Sanford White frame. I cannot recall anywhere else besides Freer Gallery display Tryon’s landscape. It is early spring: the grass is faintly green, the twig still bare, the air crisp and cold. It is a serene image, but full of energy, from the awakening of nature at the earliest dawn. I stood there long to rest my eyes, feet and mind.

Discover more from Urban Art & Antiques

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.