The exhibition “Anne C. Weary: Where the Pacific Meets the Cliffs at Torrey Pines” opened at the Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden on Friday night. Anne, who is close to 60, wore a vintage western leather jacket with twisted scully fringes on both front and back. She has a distinct look: her bright eyes speak of fortitude out of a space that speaks of the outdoors. Her shoulder-length blonde hair naturally matches the sandy color of the suede jacket; and the jacket, which made no mistakes about her Texas heritage to the audience, also led them to think about the dominant color of her Pacific Coast drawings.

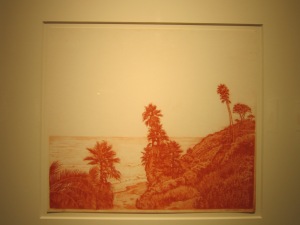

Beginning in 2008, Weary went to the Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve, almost 20 miles north of Downtown San Diego, to draw the pines, bushes, and sand dunes of California’s balmy coastlines. Still working exclusively outdoors and drawing directly from nature observed through her keen eyes, she nevertheless switched from charcoal to red conté. Speaking of her choice of medium during the opening reception, she said she liked the warm earth tones and wanted viewers to relate it to the sand.

The contrast between the white background (mostly Strathmore paper) and red conté is striking. Like the first time a Dallasite breathed in the ocean air of the West Coast after a long summer of triple-digit degree temperatures, it provides a certain chill. In the whole series, Weary chose compositions succinct and airy: The foreground and middle ground were well rendered with delicacy and detail, yet the background receded into infinity with no more than a few faint strokes of waves or the horizon line. The pine trees, with branches sprawling and spreading in a symphonic dance, retain a balance of solidity and fluidity against the white negative space.

Realistic as they may seem, the drawings are abstractions of the artist’s nature within. She admitted that she had made modifications to the scenery. More importantly, her meticulous rendering posed tremendous challenges in capturing a true plein-air atmosphere. When a visitor pointed to one of the drawings and asked how long it took her to finish, she answered about 6 to 8 weeks, closer to two months. During that period, she visited the same spot around the same time (either morning or afternoon) and continued working on the drawing to its fullness. Even though the San Diego area has almost the same weather year around (with low fog hanging in the morning before it is cleared out for the rest of the day), the nuances in clouds and sky would eventually be wiped out to neutrality after many different impressions from each daily visit stack up. Thus it is perhaps both an artistic preference and a technical convenience that Weary chose a clear background.

Several of her earlier works were also included in the exhibition. Compared to the red conté drawings, these Texas forest interiors, from either Garland or Mesquite, project a fuller sensibility through the charcoal (and occasionally graphite) medium. In many of these drawings, the exclusiveness or minimization of the sky necessitated a more subtle and varied gradient in tonality. The bushes, grasses, and limestone creek banks, all under the canopy of intensive foliage, registered a harmonious arrangement of light and shadow. While the bright Texas sunlight delineated the silhouette of trees in harsh lines, the softness in charcoal enlivened the foreground grass with a painterly velvety texture. In one particular drawing of a wintery scene, there seemed an infinite degree of grayness, highlighted by the bleak sky reflected from a pond. It was my favorite in the whole exhibition. (It was marked as sold.) The suffused luminosity through the use of charcoal has understated tranquility and intimacy that none of the Torrey Pines can rival.

As the night went deep, a handful of guests still remained with the artist. Many were fascinated by her superb drawing skills and the degree of perfection seemed to go beyond the concept of drawing itself. After all, we commonly recognize oil paintings as a manifesto of artists’ creativity for the public domain while drawings are private and mostly only have to satisfy the needs of artists themselves. But in this exhibition, each drawing was a complete finished work meant for the enjoyment of the public. The impeccable unblemished pictures left viewers more curious about her process, yet it was a pity that no additional preliminary drawings were included in the gallery. Anne talked briefly with a few visitors about the making of drawings. She started with simple outlines of the main objects. Often she drew from the middle so that she could expand around it with more freedom. And gradually, day after day, she filled in layers, solidity, and details. It was painstaking but perhaps surprised no one as most complete oil works in a representational style follow more or less the same procedure. What is amazing is the degree of confidence she possesses to make pictures in a relatively irreversible way with only red conté, stumps, and erasers.

Before leaving the Valley House Gallery, I browsed again two dozen or so drawings in the main gallery room. Looking afar, I felt those pine trees begin to float dreamily. They reflected the superlative power of the artist to synthesize geographic and flora information, yet still, there seemed to be a kind of immediacy and emotional attachment. In a tightly controlled process for public picture making, by reigning subconscious and psychological state, Anne achieved a stunning degree of intellectual revelation of nature observed.

Discover more from Urban Art & Antiques

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.